At some points, information about Chicago's Swedetown grows very faint. This is true of the story of the Methodists, who are described in passing by their rivals and we have not found a great deal about them. What we have from sympathetic sources comes from Henry Whyman in his wonderful book on the Bethel Ship Saga...we hope for more books to come from him.

Sven Bernard Nyman (Newman) from Whyman:

"Sven B. Newman arrived in New York in late January 1851 to become Hedstrom's first ministerial associate on the Bethel Ship. Invited to stay with the Hedstrom family at 4 Carlyle Street, he became acquainted with their children, Maria Elisabeth, an adopted daughter, and Wilbur Fisk, a son. (from SBN Sjalfbiografi)

We are also informed that Newman (Nyman in Swedish spelling) had been in the U.S. for some time, having a brother in the south, and that he encountered Methodism there. The specifics of his contacts with O.G. Hedstrom are as follows:

"In the early 1850's he (O.G. Hedstrom) was designated a superintendent of the Scandinavian mission by the society... It was in this capacity that Hedstrom was sent on a series of missionary journeys in the early 1850's... He arrived in Chicago before the middle of November (1852)... An unanticipated opportunity to conduct services for the Swedish community met with an exceptionally good response. After traveling the Victoria Circuit of Swedish Methodist churches with Jonas, the two brothers went to Chicago, where Olof resumed earlier preaching services, this time in the Seaman's Bethel Chapel. Here he founded the Swedish Methodist Church of that city in December 1852. On Hedstrom's arrival home, Sven Newman was dispatched to Chicago to become its first pastor."

This is the only reference we have seen to a "Seaman's Bethel Chapel" in Chicago; an interesting but unknown quantity. S.B. Newman is also cited in the history of Omaha's Swedish Methodist church.

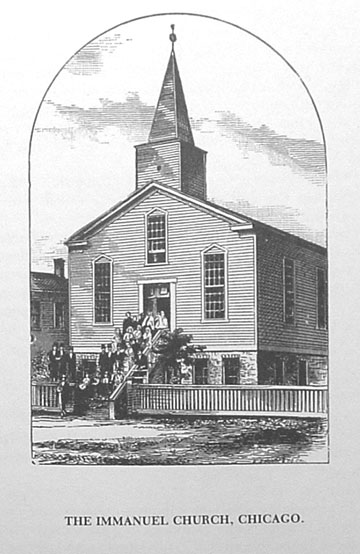

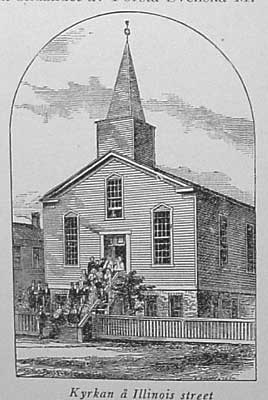

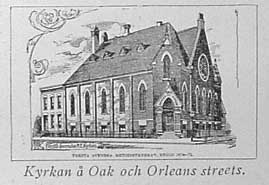

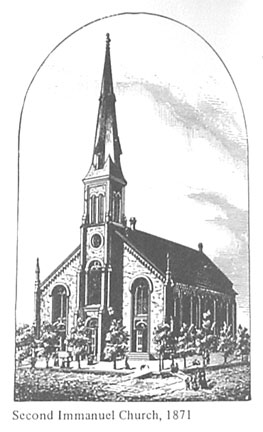

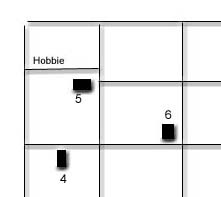

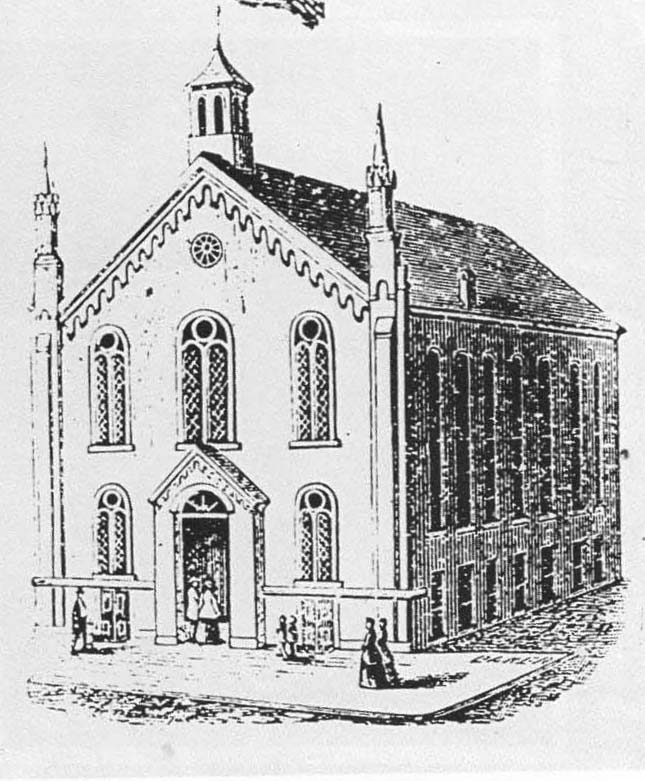

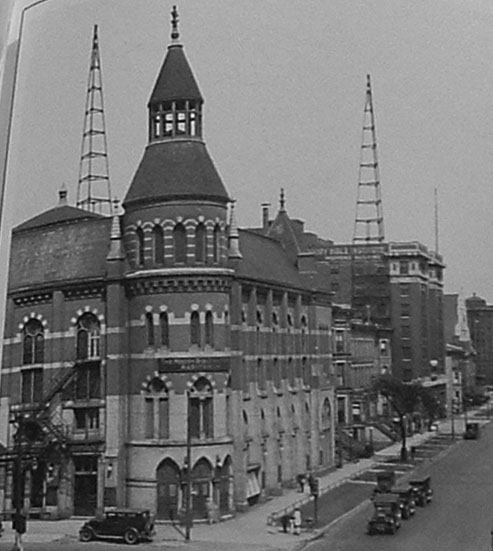

We have a rendition of the early Chicago Methodist church "on Illinois Street" from Wallinius/Liljegren, but very curiously it appears to be the same view supplied by Bergendoff's edition of Norelius' "Swedish Settlements", there claiming to be the Superior St. Immanuel church! The same view appears in Emory Lindquist's book about Erland Carlsson. The Methodist's Illinois Street attribution is by far the earliest, for what that is worth.

Who is right?

Norelius' own memoirs have this to say about Newman:

"Father Nyman," as he now was known (1854) was at this time serving the Scandinavian Methodists in Chicago. Father Nyman was a somewhat eccentric man, pious and sincere according to his convictions, a thorough ascetic."

The irenic Erland Carlsson, long time pastor at Swedetown's Immanuel Lutheran church has these comments in the publication "Korsbaneret", reported by Emory Lindquist:

"The congregation and I had very good relations with the Methodists at the outset. We visited personally and attended each others meetings." Pastor S.B. Newman of the Swedish Methodist Church and Carlsson worked effectively together during the cholera year 1854. But two obstacles developed which detracted from this era of good feeling according to Erl. Carlsson:

"1. The Methodists began to exert efforts to attract Lutherans to their congregations.

2. The Lutherans became almost scared over the manner in which the Methodists converted people, whereby as soon as they could get anyone to stand up and go to the 'mourners bench' or altar to receive prayers in their behalf, that person would then be declared to be converted and won for Christ. They had the custom of praising God and declaring how many people had been converted that evening and had become children of God."

We have observed how similar were the practices of the Mission Friends and how Carlsson's successor Evald described Immanuel "after meetings" as the context for many becoming "children of God." The influence of the American style of revivalism was sharply felt by the Swedetown churches. Did the proximity to Moody's church figure in this?

Later,"The Methodists and Lutherans lived peaceably side by side until 1861 when the Methodist pastor, A.J. Anderson, presented a lecture in which the differences between the two denominations were clearly emphasized. The critical nature of the presentation caused the deacons of Immanuel Church to request Carlsson to repond to what they viewed as an attack upon Lutheran doctrine."

We find new meaning in the phrase, "side by side" when discovering that the two churches were only a block or two apart in Swedetown!

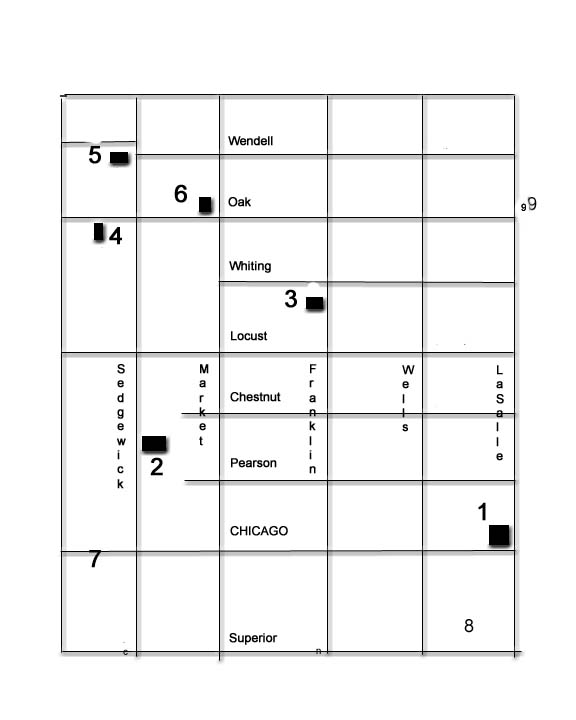

To the left is Swedish Methodist, to the right Immanuel Lutheran

5 is Immanuel, 6 is Methodist (4 is Baptist)

MOODY AND SWEDETOWN

We heartily recommend David M. Gustafson's (hereafter DMG) work on Moody and the Swedes as the benchmark for the subject both here in the Chicago Swedetown and throughout America and Sweden.

D.L Moody, J.V. Farwell and Chicago kids

To that we add but one simple fact: by 1938 figures, 50% of the membership in Moody church was Swedish! (p. 143 DMG)

We particularly like DMG's use of the term "smörgåsbord" to describe the church options open to the residents of Swedetown. It seems that most Swedish immigrant settlements offered these "choices." But we wish it had not been a smörgåsbord in which one group took only, say, meatballs and then went to the meatball eaters' table and looked askance at the herring eaters.

We cannot resist a quote from M.W. Montgomery, the Congregationalist who wooed so ardently the Swedes, from his book A Wind From the Holy Spirit in Sweden and Norway." (this book is now available but in a poorly done computer text-recognition version) Montgomery is experiencing his first Swedish smörgåsbord and it has a feature quite foreign to us Mission Friends:

"In the beautiful dining room of the Grand Hotel (there is no better kept hotel to be found anywhere), on a side table where the "smärgäsbord", (pronounced 'smar-gos-boord) is kept, there is a barrel-shaped silver tankard, about two feet long, in which are six faucets, from which may be drawn as many sorts of strong drinks and to which all who go to that table may have free access."

At any rate, Chicago Swedetown is a smörgåsbord for us historians. A rationale for Swedetown's attraction to Moody comes from the forebear of a personal friend connected with Princeton, Illinois; that forebear was Rev. C.F. Pamp. For this reason we are inclined to give special attention to what he says:

My father came [to America] in 1869, my mother in 1870. They were in the great fire in Chicago in 1871, in which everything they had gathered together was swept away. Those years were the great years of D. L. Moody’s work in Chicago. He had gotten his Sunday school and church going, and it was exerting a tremendous influence. I was born not far from the Moody church in Chicago. Those first years, before the Swedish people had the opportunity to build their own churches and establish their own worship, Moody opened his heart and his church to them, and he addressed them, and they understood Moody’s English. My father often told me that he had difficulty in understanding English, ordinarily, but when he heard D. L. Moody speak he could understand him. ... Here was a man who opened his heart and his church to them, and spoke to them out of the fullness of his experience of Christ, and even if they did not understand all that he said they understood his spirit and his warm heart.

Two earlier Moody sites: the Illinois St. church which burned,

and the tabernacle hall both to the south of Chicago Avenue

The practical example of compassion for the unfortunate, which we saw before in Moody's willingness to find a priest's coat for John Peterson, would have been powerful. Gustafson has filled in for us details of Moody influence extending back to Sweden itself through the English revival meetings and the translations of his works into Swedish. Again, from C.F. Pamp:

I was speaking with a Swedish man here [in America] who told me that he remembered distinctly in his home in Sweden that almost everybody among the common people had copies of the sermons of D. L. Moody and the songs of Sankey in their homes. …They met in little groups in homes, and had someone who would read to them, preferably the sermons of D. L. Moody, and then they would sing Sankey’s songs. … and men and women were converted to Christ in these little gatherings. The men who did the reading to the people were called in Swedish “Läsare,” readers. … We cannot measure the influence of D. L. Moody’s sermons and Sankey’s songs in the tremendous revivals that spread into the most remote regions in Sweden.

Moody's initial work with the children of Chicago's poorest citizens in independent, non-denominational form was something of great merit. It is also to his credit that his phenomenal success was never meant to be turned against existing denominations and that he was successful in keeping his own name from being institutionalized, at least until after his death. Only then did the Chicago Avenue church become "Moody Memorial Church", and the Chicago Bible Institute become "Moody Bible Institute." Even the formation of a church came later in his ministry, after the success of the English visit and campaigns in the east. The building of the Chicago meeting hall and the results of his preaching there convinced him that a church should be built. But by then, he was taking his ministry "on the road" and was not typically present at the church which would ultimately bear his name.

Three Swedish Moodyites: J. Okerstein, Fredrik Franson, John Martenson

Three Swedes who were members of the Chicago Avenue church came to prominence. John F. Okerstein came to Moody's attention in the days of the earlier Chicago meeting hall and became his city missionary for Scandinavian work. As this work expanded at the Swedetown Chicago Avenue location, Okerstein was in charge of arranging meetings for the Swedes, though now under the pastorate of Wm. Eerdman. The Sunday school ministry for children remained central and had impressed Swedish Mission leader C.J. Nyvall on an American visit. In preparation for the Chicago campaign following the overseas revivals, Okerstein's workers canvassed "every home, business, bar and billiard hall" along Chicago avenue!

The second was Fredrik Franson, who came to Chicago from the secluded little Swedish Baptist church of Estina, Nebraska (a building which still stands...see Saunders County section). It may be truly said that Franson was "on a mission" and he became the first missionary sent out by the Chicago Avenue church. It is not possible to condense his ministry to a few words, but he literally went around the world. Enter his name on your favorite computer search engine, and you will find page after page of references, some in foreign tongues! He, too, resisted having his name wedded to any institution.

The third we mention is John Martenson, the journalist who was transformed by the Moody/Skogsbergh campaign into the leading advocate for Free Mission ideas through his powerful instrument, Chicago-Bladet. He published Moody's sermons and Waldenström's books, bringing them into the homes of Swedish immigrants across America. He employed the "unchurchlike" polemic style of American political journalism which Swedish denominational churchmen smarted under for years.

To set the context, what was the impact of the Moody phenomenon on the other denominational congregations in Swedetown? Later we intend to examine how the unique setting of the Chicago Moody "chapel" (there is resistance to accepting the "church" label) can be translated into village and countryside in other communities. As for the Swedetown churches, we have shown evidence that some Moody methods came to be employed even in Immanuel Lutheran church! We will point to a few "growing pains" for the Swedes at Moody church, but first to assess how the other Swedetown denominations viewed Moody.

The largest stakeholder among the Swedes would have been the Augustana group. They were strong enough to be bold in confronting the "sectarians" no matter how much like "motherhood and apple pie" they might be. Immanuel evidenced some innovations in method that may have had Moody origins, and they also were occupied with their own revivalists, the Mission Friends.

The Baptists have no recorded animosity towards Moody; in fact they relied on Moody workers to conduct their own Sunday school. But Baptists would never condone the sprinkling of infants that was allowed in the Chicago Avenue church. Nevertheless we have seen the picture of their jubilee festival at Moody's; it may have been a sentimental last return to Swedetown since by this time the Baptist church there was closed.

Methodists for all their similarities in belief and practice had a system in place that approached membership with greater caution than "instantaneous conversion" implied. They were veteran revivalists, and not inclined toward the immersion tank for "believers' baptism" at Moody's. We have no specific data.

Covenanter David Nyvall gives the a most candid statement from a somewhat later period as President of North Park College, but he might have spoken for each of the Swedetown congregations:

"Mission Friends in larger and larger numbers were led to associate themselves with what was later called Moody church and then became attracted to the Moody Bible Insititute, in preference to their own churches and their own school." (The Swedish Element in America p. 154)

Evangelistic campaigners from Moody to Billy Graham have given lip service to their converts to return to their own churches; they seem innocent to the thought that their campaigns imply severe deficiency in those churches.

The impressive Chicago Avenue church at LaSalle Street

The "growing pains" were entirely predictable. As the Swedish meetings grew in size and scope there was pressure on the administration of Chicago Avenue church to accommodate them. In some cases, there had to be refusal of such accommodation. When application for the scheduling of a full-scale "mission meeting" was refused, the Swedish member of the administration tendered his resignation.

Earlier, an "inquiry" was held into the doctrinal positions held by Franson. The "Waldenströmian heresy" was in the papers, but Franson was able to aquit himself. Martenson, however, was ready to "try something new" and the chapter of the independant Free Mission Friends was about to open. That is our next section.

The Chicago Avenue church gravitated toward an emphasis on the "end times", especially true of their missionary Franson. We would mention only one example from DMG:

Franson’s sermons and books fanned the eschatological flames among Mission Friends at the end of the nineteenth century, and influenced others such as John Ongman of Örebromissionen in Sweden.

“Many readers believed that Christ’s return would happen on Easter, 1898. People said goodbye to relatives and friends and clothed themselves in white clothing. It happened that on the eve of Easter they gathered in a church yard in order to witness Christ’s return, and along with those who were resurrected from their graves, they too would be snatched up to meet Christ in the air (1 Thes. 4:16, 17).”

The same Ongman served the Chicago Swedetown Baptist church two different times, but we cannot say with certainty how much of his adventism originated with Moody's.

The emphasis on the notion of the second coming and its proximity followed for Moody and the Swedish Moodyites on the simple equation that it is mentioned fifty some times in the Bible, while such things as baptism are less frequently mentioned. Attributing traditional titles to this emphasis (chiliasm, imminent parousia, Darbyism) may fail to clarify the issue, while an example from American religious history might.

"While Adventism as a religious phenomenon has been found in every period of Christian history, the existing Adventist churches in America trace their origin to the preaching of William Miller, a Baptist minister, who predicted the end of the world in the early 1840s. Miller was a farmer whose studies of the Book of Daniel convinced him that the second coming of Christ to the earth would take place between March 21, 1843 and March 21, 1844. He preached his first Adventist sermon in 1831, and by 1844 an estimated fifty thousand followers anxiously awaited the imminent Parousia." p.30 J.A. Hardon, The Protestant Churches of America.

Adventists soon learned to be more vague about the actual date, but this did not deter their credulous following both within their own ranks and among all "millennialists." The recent popularity of Tim LaHaye indicates the perennial appeal of this curious phenomenon.

Growing up in a Swedish community in Nebraska after the second world war, "Moody fever" was pretty much something of the past. We would learn later that our wife's confirmation pastor had taken his training at Moody Bible Institute (mine was a graduate of the Risberg Swedish Congregational school). In our Mission church, there was little mention of Moody and we might add, little mention of fundamentalism or Calvinism either.

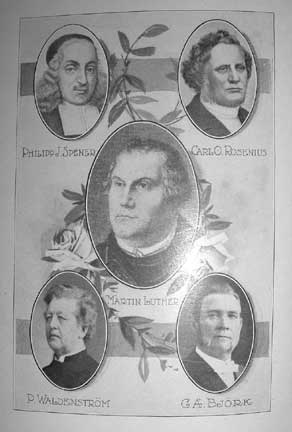

The Swedish Mission Association of Nebraska 1912 book frontispiece

Moody, Franson, Skogsbergh: not present

Luther, Rosenius, Björk, Waldenström: present

But there were evidences, looking back, that may be significant. The name chosen by my home church was "The Swedish Christian Congregation of Wausa, Nebraska." This choice no doubt reflects the counsel typical of Chicago-Bladet. My wife's church was "The Church of God at Westmark, Nebraska", and Franson's portrait is seen on its wall..."our missionary founder." At the times of our births, neither congregation belonged to a national organization. At one time, pastors from both attended meetings of the Nebraska Swedish Lutheran Mission Association, later to become the Midwest Conference of the Covenant. Now, Wausa is a member of the Covenant and Westmark is a member of the Evangelical Free Church. And we might add that upon coming to Chicago from the farm in 1961, it was a familiar comfort to awaken to Wilbur Nelson's "Morning Chapel Hour" on WMBI radio. M.R. DeHahn, however, seemed a little "over the top."

It is a simple fact that a Moody style ministry does not translate well into the small communities of Swedish immigrants that made up the rank and file. Such a church might be chartered and built, but it would come out looking just like the other Swedish churches in the community. There is neither the empoverished class of the urban setting nor the masses required for an evangelistic campaign. On the other hand, a very Moody-like organization, the Swedish Salvation Army, did penetrate to many of the midwestern settlements we have visited. The YMCA, with which he and some of his Swedish following were heavily involved, seemed destined to go in another direction.

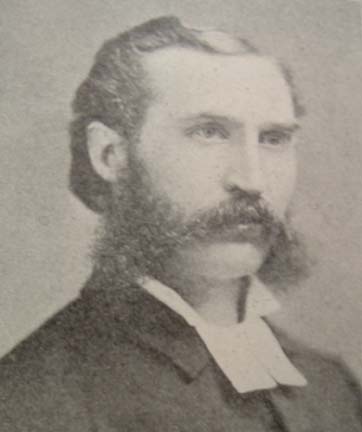

E.A. Skogsbergh: "The Swedish Moody"

We have neglected to mention one figure who was impacted greatly by Moody: E.A. Skogsbergh. Coming to Chicago and preaching in the Swedetown Mission church on his first day, he not only heard Moody but was satisfied with no less than becoming his imitator. He famously was called "the Swedish Moody", and did nothing to shrug off the title. A Mission group taking shape on the south side became his field, and he soon had built a tabernacle there in the Moody style. He preached in the Mission church circuit with great effect and before long had left Chicago behind, to build tabernacles in Minneapolis and later Seattle. These last two still stand. He came through Swedetown like something of a storm. His was not the typical style but his results could not be questioned. To read his memoirs is to see first hand what an entertaining and amusing observer he was. Though independent by instinct, he cast his lot with the Covenant in 1885.

The uniqueness of Moody's did not translate well, but it must be noted that this work is one that survives in old Swedetown right up to the present day. Furthermore, Moody himself was not favorable to the idea of "another church." Neither was Franson. But Martenson and Princell moved ahead.

THE SWEDISH FREE MISSION

His Princeton, Illinois Augustana pastor had seen in young John Gummerson a bright and promising believer, one he endorsed to become a student for ministry. We have followed his course to Chicago's Swedetown and his collaboration with Immanuel's Erland Carlsson. He takes the name Princell from Princeton.

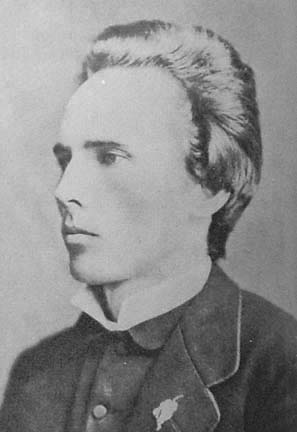

J.G. Princell

To read his biography, written by his talented wife, Josephine, herself an articulate leader, is to be utterly fascinated by a unique character. A man who was enthralled by ideas and their expression, he exemplifies the image of the "professor", one who lives in a world slightly apart from the pragmatic leaders of churches and who often exasperated them. He also would have understood the English language perfectly well, and have recognized that Moody did not speak it eloquently.

As in the case of Franson, it is impossible in a few lines to follow the tortuous course of Princell's career. On the east coast, his insistence on regenerate membership causes irreconcilable differences with Augustana. His taking charge of Ansgar College in Knoxville, Illinois, also comes to a bitter end for a variety of reasons.

Again without a job, he joins John Martenson at Chicago-Bladet. They seem to be in agreement that Waldenström is the key to the future for Swedish Mission Friends in Sweden and America. And he is very newsworthy. They also have arrived at the near-utopian idea that the Swedes might lay aside their embryonic denominational parties: Methodist, Baptist, Mission Synod and Ansgar Synod and be joined in one New Testament spirit of cooperation.

At this point of confluence between Waldenström in Sweden and Moody in America, they extend a call through the organ of Chicago-Bladet for a series of Mission meetings in which the nature of the church, and the prophetic light the Bible might shed on the end times would be discussed. We have always been amazed at how mobile these early Swedes were: they came from throughout their American diaspora to these Mission meetings.

Number #9, upper right, points eastward on Oak street

This series of meetings and their fallout defined the emerging Covenant and Free groups, and we suspect that the verdict of E.W. Olson in The Swedish Element in Illinois could stand for most observers: "The lines of demarcation between these (Covenant, Congregational, Free) cannot be distinctly drawn." (p.583) For the full story see DMG's translation of the Boone 1884 meeting.

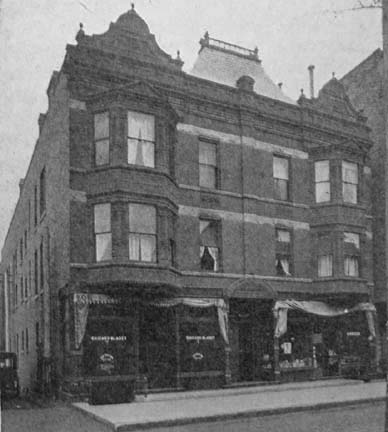

Practicality dictates that renting public halls is less convenient or economical than their ultimate solution: meeting in the Chicago-Bladet publishing house. This is soon to be rebuilt in expanded form on Oak street, and a meeting hall is part of the plans. Number #9 on the map points to the direction in which the "Oak Street Mission" lies to the east. No less a personage than Waldenström himself is present at its dedication. Very much a store-front in appearance and fact, it becomes the first Swedish Free Mission church in Chicago. By no means a "former store", it is very much in operation as Chicago-Bladet publishing house, and Martenson is the proprietor.

Oak Street Mission and Chicago-Bladet Publishing Company

The Swedish religious publishing field warrants a story of its own, but we can only touch on it here. Virtually all of the denominations began by being served by independant publishers and each had its own headaches. Many if not most were at some point located right here in Swedetown. Eventually each denomination gained control of its publishing, including the Free Mission church which adopted its advocate, Chicago-Bladet.

Concerning the work of Princell and especially Martenson and Franson, I have been struck by the following passage from Williston Walker's History of the Christian Church. He is speaking of some of the events of the "great awakening" in America:

"The Presbyterians were also torn by controversy. Those, often of Scotch-Irish background, who held firmly to confessional standards and to traditions of an educated ministry were sore troubled by frontier revivalists whose doctrinal emphases and ordination standards were more lax. In 1803, Barton W. Stone (1772-1844) led a group of evangelistic Presbyterians out of the Synod of Kentucky. These "New Lights" soon dropped all "sectarian" names, seeking to be known simply as "Christians." Several years later, attempts to discipline Cumberland (Kentucky) Presbytery revivalists led to open break, and the formation of what became the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. Some of the smaller Presbyterian bodies suffered schism too. Thomas Campbell, a Seceder Presbyterian minister in the north of Ireland, came to America in 1807, and began work in western Pennsylvania. Here his freedom in welcoming Presbyterians of all parties to communion aroused criticism, and he was disciplined by the Seceder Presbytery of Chartiers. Campbell felt it his duty to protest against such sectarianism, and to assert as the standard of all Christian discipleship the literal terms of the Bible alone, as he understood it. Thomas Campbell now broke with the Seceder Presbyterians, but continued to labor in western Pennsylvania, announcing as his principle: "Where the Scriptures speak, we speak ; and where the Scriptures are silent, we are silent." It was not a new denomination that he planned, but a union of all Christians on this Biblical basis, without added tests of creed or ritual. In August, 1809, Thomas Campbell organized The Christian Association of Washington -- so-called from the Pennsylvania county of its origin -- and for it he prepared the "Declaration and Address" which has since been regarded as a fundamental document of what was to be known as the Disciples movement." (p. 512)

To this we can only add in paraphrase, "those who are unaware of history are very likely to repeat it!" Perhaps one of the most valuable things about training for ministers is the review of ancient heresies, so they may recognize them when they recur! At this time Princell and Martenson were engaged in what we today might call a "media blitz" on the pages of Chicago-Bladet. They were condemning all forms of denominational organization as unscriptural. Sharp attacks against the Augustana Lutherans had been the stock in trade for some time, but now the same weapons were trained on those who sought a new union of the Mission Friends' Mission Synod and Ansgar Synod.

One theory holds that the organizational meetings that resulted in the new Covenant deliberately avoided confrontation with the anti-synodical forces. It is true that when the formal organization of the Covenant took place down on the south side of Chicago, Princell was denied participation. But of the non-denominational concept itself, we are struck by the similarities in the paragraph above. It begins with distress at church divisions; it claims to apply only Scriptural criterion to church polity (suggestive of Waldenström's ideas), and calls for the "union of all Christians." It also resulted in yet another denomination.

Oak Street Mission regulars

The present Evangelical Free Church traces its origins to these events surrounding Princell and Martenson, based in Chicago's Swedetown. Free Mission pastors received schooling under Princell at the Oak Street Mission. He was assisted by Axel Nordin, who also founded the Phelps Center, Nebraska children's home near my wife's home. The Oak Street Mission initially had no formal minister, but C.O. Sahlström often preached there. He also figured in a temporary split of the Princeton, Illinois, Mission congregation due to his perfectionism and charismatic methods. Still later he is state missionary for the Free in Nebraska, perhaps somewhat mellowed. Eventually Princell would move the school to Minneapolis where our great uncle Hugo Rodine would be among his last students. So in fact, the roots of Augustana Seminary, The Bethel Baptist Seminary, and Trinity (Free) Seminary all trace through Chicago's Swedetown. Swedish Methodist Seminary of Evanston and North Park (Covenant) Seminary, were not far away.

Swedetown from space: the area today with the locations of the churches

Moody bookstore and St. Matthew Methodist the only remaining sites (1) others:

(2) St. Ansgars (3) Mission (4) Baptist (5) Immanuel (6) Methodist

As the Monty Python players and our Old Testament professor Fred Holmgren often said: "now for something completely different."

We have now identified each of the points illustrated on our map. We would like very much to take a walking tour of old Swedetown some fine summer day to see just what it looks like now. Anyone care to join us? But there are other historical sites nearby as well. Walk three blocks east along Chicago Avenue from the Moody bookstore and you will come to Holy Name Cathedral, seat of the Chicago archdiocese. High above you can see the red hats of former Cardinals hanging, including John Cardinal Cody's who was there during our school years. Across the street was the Schofield Flower shop, headquarters of Dion O'Banion and the "north side gang". Yes, this is the location of the "handshake murder" and other gangland assassinations during the Capone era.

The gunshots would have been audible in Swedetown!