In the year of our internship at Princeton Covenant church, that congregation was celebrating its centennial year. We had no idea how many threads from this experience would carry through our lives!

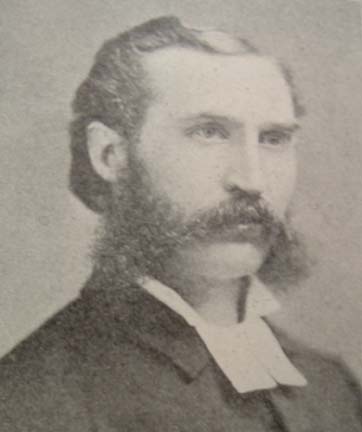

Eric Norelius

From that year onward, whenever the Princeton name appeared in our reading it had special interest and meaning…and that was often. Eric Norelius was a young immigrant in his earliest encounter with Princeton and his story is interesting. He became one of the most prominent and earliest of the Swedish Augustana Lutherans’ historians. The date is November 21, 1850.

My brother and I, together with Anders Westerlund and Anders Wadlund of Bergsjö, continued on our journey. Finally we came to an open plain where we saw in the distance a few houses that were supposed to be the city of Princeton.

A short distance southeast of Princeton we came to a river. There was a bridge across the river, and here an accident had happened. One of the livery wagons that had passed us early that day had tipped into the river when two drivers had been racing to see who could get to the bridge first. Both had reached there at the same time and one team was crowded off. The wagon with its load of goods and people tumbled into the river, and this was quite a fall. When we came to the place we found that it was old Anders Westerlund and his family. His wife and their daughter were quite seriously injured, but Westerlund himself most critically. When the load tipped he tried to jump and struck his head against the edge of the bridge with such force that he fractured his skull. At first he did not seem to realize the seriousness of his condition, and he walked the rest of the way to Princeton. When we arrived there in the evening he sat outside the tavern, complaining about his head.

We had some difficulty in securing lodgings. Except for a small rooming-house, which was just a ramshackle building, there were only a very few houses in Princeton at that time. The only Swede then living in Princeton was Eric Wester, the great adventurer, who had a little barber shop there, but he was not able to give us any help…

At last we happened to meet a young Swedish farm laborer, who had come from Östergötland, and who now worked for a minister about a mile and a half from the village. The young man thought that the minister would let us stay in his barn over night. We had no choice, so we gratefully accepted the offer and proceeded to the place.

A. Westerlund and his family were taken into the kitchen, and there the old man died during the night. The rest of us, including several small children, went to the barn and cuddled up in the hay, trying to keep warm. It was a very cold night, and in the morning we were so stiff from cold and weariness that it took a long time before we could get up and stand erect.

The body of Westerlund had to be left at the place, and the minister agreed to arrange for the burial at a cost of ten dollars.

Some of those traveling on foot and also some who had hired teams decided to stay in Princeton, and they became the nucleus of the Swedish population there. Among these were Hans Smith, Olof Nilson, Anders Larson, Anders Nord, Olof Janson, Stefan Berglöf, Hans Kamel together with their families, and various others. The rest of us, after having bought some bread in Princeton, continued on our way, but we suffered from the cold and from sore feet…

On November 23 there was a severe snowstorm, and it was quite cold. Late in the afternoon we arrived at Andover…

November 24. – In the evening I went to visit Rev. Esbjörn, who lived a mile and a half from where I was staying, south of the tract of woodland that extends east and west. I found that Anders Ersson of Gnarp and Joris Per Anderson of Hassela had rented the largest room in Esbjörn’s house, the room which had been intended for a kitchen. This was the first time I saw Esbjörn. He was teaching geometry to two young ladies of American birth, daughters of one Pillsbury, who had formerly been a minister. Esbjörn was dressed in a ragged old Swedish clerical coat. Everything in the house testified to great poverty. (Early Life of Eric Norelius, p114ff.)

Thus we have the account of the first meeting of two of the greatest founders of Swedish Lutheranism in America! And in what modest, if not to say dire, circumstances! Norelius would see unbelievable progress in his time, and surely relishes the contrast with the hardships of the beginnings. The facts he mentions will have later significance: the first Swedes to come to Princeton; that “character”, Eric Wester, whose name comes up time and again as a perceived problem in the Princeton Lutheran community; and the primitive landscape devoid of railroads and population.

In 1852, Esbjörn’s own memoirs contain the following:

“In June I visited Princeton, Bureau County, where some Swedes live. On several occasions they had asked me to come and break the bread of life for them. When I got there I found that another Swedish preacher from Chicago (Unonius) had been there and conducted Holy Communion. But those who were pious (!) had not participated in the Communion, since they considered him to be an unconverted man. They received me, therefore, with great joy, and I had an inspiring time with them.” (quoted in Ronnegard, Pioneer Shepherd, p. 173)

The remarkable influence of Episcopal minister, Gustav Unonius, extended from Chicago as far as New Sweden, Iowa, and can be found in the website sections on those places. It is also remarkable that the Princeton devout were at this early time so discriminating in their communion practice, and that Esbjörn met their standards! The exclamation point in the quote indicates that he also considered this remarkable.

Southeast Settlement schoolhouse; home to the mission friends

“Eric Wester, according to Svenskarne i Illinois, had the name Westergren. It is not known when he left Sweden, but rumor has it that he was a guard at the Swedish Bank in Stockholm, was sent to Helsingor once to buy a large supply of material for the paper factory at Tumba where the bank’s paper was manufactured, and that he absconded to America with the money. His career in America is in accord. He seems to have appeared first in New Orleans. There he shaved Scandinavian seamen – on his barber shop the sign read – “come let us test how Swedish steel bites.” In 1848 he was in Bishop Hill but didn’t stay very long. Then to Pine Lake, Wisconsin where, according to Unonius, he gave the impression for a short time of being spiritually interested. From Wisconsin he moved to Princeton and opened a barber shop. “He was,” says Svenskarne i Illinois, “full of initiative and tricks, and he soon discovered that Princeton was as good a place as any to use these traits. A rich tradesman helped him get a stock of cigars, and he opened business in a shanty. Watered with whiskey the plant took root, blossomed and bore fruit. As the affair took on greater dimensions it required soon larger space. Now it included almost everything: clothes, food, shoes, hardware, tobacco, whiskey.” It progressed, a branch was established in Galesburg, he joined the Bishop Hill colony in a bank deal. Then he failed. He tried his luck again in 1858, but with no better success. In 1859 he declared bankruptcy, but seems to have had enough to pay his debts. “With $1,700 and a trunk full of revolvers he set off for Chicago, he said, but landed in Dallas, Texas. He is supposed now (1880) to be there, in poor circumstances.” Were one to write about Swedish adventurers in America, Eric Wester would certainly deserve a chapter in it.”

And so, we have followed Norelius’ cue and included him. But to some amazement, in the list of charter members for the Princeton Lutheran church organized in 1854 by pastors Valentin and Esbjörn, we find Wester’s name. Princeton seemed to be plagued by some “shaky” ministers when it could attract any minister at all. Valentin leaves suddenly that fall for Sweden. After a time, Esbjörn serves the congregation briefly though he is ill. At that time the congregation very deliberately adopts a constitution.

Another charter member is Jacob Nyman. Norelius does not connect him with a subsequent pastor, the son of Per Nyman, nor does he spell out any relationship to “Father Nyman” of the Chicago Swedetown Methodist church, but in any case, this Nyman is not Synod-approved. His tenure is short, to Norelius’ relief.

Next comes C.J. Vossner, of whom we read the following:

“When he heard that there was a vacancy in the Swedish congregation in Princeton he appears to have written to Eric Wester offering to become its pastor and to have received a favorable reply. He loaded all his belongings – clothes, clay pots, wash tub, wooden shovel, rifle – all on a wheelbarrow and started on the adventurous journey, first by boat across Lake Michigan and then by train to Princeton where he arrived safely and well. E. Wester was enthusiastic and did all he could to have him accepted by the congregation. Vossner read his old, yellowing sermons, and Wester turned around in his bench to see what was the effect on the members, groaning when he noted that they were not impressed. When Vossner went up to Wester to learn what his prospects were he received the crushing reply that they were poor. Walking back and forth on the floor, in his dressing gown, he told him, “I regret it. Pastor, I feel sorry for you Pastor, but the people don’t like you, they say the pastor preaches trash.” The poor Vossner had to depart as he came, taking along his wheelbarrow to Chicago.” (Pioneer Swedish Settlements p.206)

If Norelius had continued his account beyond 1860 there would surely be more interesting stories to read about. Particularly, what caused the congregation to split over the new Augustana constitution in 1870, or what prompted the exodus of another eighty to form an Ansgar Synod congregation in 1883. That information comes from the history of the Princeton Mission congregation, which had left the group in 1868 and will be detailed later. Princeton Swedish Lutherans had certainly had their troubles.

Author of the 40th Anniversary history, C. J. Ledin

The Covenant church which hosted our internship in 1968 was the successor to the Mission association just mentioned. Among our inheritances from that experience is a copy of their 40th anniversary book including a history of the congregation. Since the Princeton congregation is counted among the first four Covenant churches founded in America, much has been written about it. The Swedish revival movement transferred itself to the immigrant community. Swedish mission friends replicated their organizations in the new land. The first organization at Princeton was a missionförening, or “mission association” which in Sweden would have been an adjunct to the parish state church. The members of this association were at first members of the Princeton Swedish Lutheran church. But the situation in Sweden was changing. The mission associations were gaining more freedom and independence, even to the extent of holding their own worship and communion services outside the state church. In America’s context of religious freedom it was inevitable that the same thing would happen here, even though the Swedish Lutherans had been much influenced by the revivals. The leaders of their Augustana Synod had been assailed by proponents of Swedish Methodist and Baptist groups and were “circling the wagons” against competing denominations. (Norelius reports that both these groups had checked out Princeton early on, but only later would extend efforts to start congregations there)

J. G. Princell and the family gravesite at Assaria, Kansas

Before leaving the subject of Princeton’s Augustana church, its most famous son must be mentioned. When the Gummenson family arrived from Sweden, the Lutheran pastor (and we do not know which one) found in young John Gustaf a bright and promising student. On his recommendation, John was enrolled in Esbjörn’s new school. His academic career blossomed, and his fondness for Princeton resulted in his changing his name to honor that hometown: Princell. His parents moved from Princeton to Assaria, Kansas, in the Lindsborg vicinity, and we visited their graves this past summer. While conducting his school for Free Mission pastors in Minneapolis, our great uncle Hugo Rodine was among his last students. We knew none of these things in 1968.

The mission friends movement in Sweden was one of laymen ministering to other laymen, and no history of Princeton’s mission friends omits the account of S.P. Lundholm exhorting his neighbors. Jonas Person famously jumped over a fence to tell Lundholm that his soul, too, had found release.

C. P. Mellgren in America, and at Sunnerbo Härad, Sweden (before a name change)

Shortly, C.P. Mellgren came to Princeton. He had been a colporteur, or traveling representative of the Sunnerbo Mission Society of Småland, and so had some training and was experienced in this kind of ministry. Now Princeton’s association had a leader who could formally organize them, which was done on December 14, 1868. These mission friends were located in a community five miles southeast of Princeton. If it had a name, it is unknown. They were members of the Swedish Augustana church in the town, and given the difficulties of that congregation that we have enumerated, might well have entertained hopes that their vision of a Swedish-American church would prevail in that Lutheran congregation. Something resembling that would happen in Boone and Des Moines, Iowa.

But the centralizing forces of Augustana’s leadership, having been put upon by Methodist and Baptist campaigners elsewhere, was not about to condone a rift within. Pastor Lindholm visited the mission house and lectured the friends on the dangers of separatism and the virtues of Lutheran orthodoxy. Unfortunately, in so doing he and many of his colleagues in Augustana reminded the mission friends of the attitudes of many Swedish state Lutheran priests. Cautious as they were, a resolve not to capitulate in this new opportunity for freedom grew into a movement among the mission friends.

Princeton ordföreståndare C. G. Swanson

But it did not happen overnight. When C.G. Swanson met with other representatives of mission associations in Chicago and Keokuk, Iowa, to form the Mission Synod, Princeton joined as a mission association, not as a church. The same would have been true of the associations of Chicago and Swede Bend. The heated debates over the relative merits of organizing as föreningen (associations) versus församlingen (congregations; churches) would echo for years among the mission friends and may have anticipated the fria versus bundna controversy in later decades. It is easy to dismiss the warnings issued by Unonius and later the Hasselquist loyalists today, but evidently the Swedes were unnerved by them. Another distortion time has wrought is the relative role of the colporteur and the ordföreståndares (chairman; sometimes even “pastor”). Notice that it is C.G. Swanson, Princeton’s chairman for decades, who represents the association and receives the office of treasurer of the Mission Synod at its charter. The early mission friends were wary of creating a “guild” of clergymen. (a number of C. G. Swanson's children relocated to Aurora, Nebraska... the "Princeton Settlement.")

Not many years ago, we happened on a copy of the history of the Sunnerbo Mission Society from Sweden in an Omaha used bookstore. Included were pictures of their colporteurs, C.P. Mellgren and Peter Wedin, who was also to come to Princeton and succeed Mellgren when the latter moved on to Kansas in 1873. Wedin is of particular interest because of his reaction to developments in the Skogsbergh era and of his later career in Nebraska.

A remarkable book find

On the pages of Sunnerbo’s story, one familiar name that appears is Oscar Ahnfelt. He, and the Sunnerbo group which looked to him as one of their founders, was opposed to separation from the state church. These loyalists belonged to the E.N.F; the “approved” group for revivalists and mission minded Swedes. They are aware of the Swedish Covenant, and note that some of their former preachers have gone that way, but they have not. This might provide an insight into the mindset of Princeton’s first pastoral leaders, Mellgren and Wedin. Separatism should not have been an issue in America; for all the posturing of Unonius and the earnest efforts of Augustana to “be” the Swedish church in America, it was a country free of established religion and separatism should have been a dead issue. But somehow it was not.

There are other interesting items in the 1908 history that disappear in later versions. A point-for-point explication of the Waldenström atonement doctrine, is one. Names such as Princell and Franson are others. Princell appears at an 1869 mission meeting, held in the Augustana church. It is noted that he is a Lutheran student, a native of Princeton in his youth, and that he “sides” with the mission friends. The 1909 writer does not have specifics from that meeting, but interpolates the heated exchange of a contemporary meeting at Immanuel in Chicago when Augustana and mission proponents clash “sharply.” By the next year, the Princeton “southeast settlement” mission people are reprimanded, and hold their mission meeting in the American Lutheran church.

Princeton church in 1908

Skogsbergh called it "a shining city on a hill"

no known picture of the earlier missionhouse in town has been found

No longer feeling welcome with Augustana, the friends build their own missionhouse in the town of Princeton the next year. Now any hopes of shaping the Swedish church of Princeton are fading, but large numbers of new immigrants sharing their mission friend persuasion cause the mission house to become too small. Changes were being forced upon the friends and those changes would accelerate with the visit of Skogsbergh in 1877.

Before opening that chapter, let us trace the movement of Pastor C. P. Mellgren to Kansas. Osage City and Stotler are a town and country pairing; a “binary star” situation not that uncommon among the early churches. Osage City is an old coal mining settlement of mixed ethnic origins and Stotler a rural farming settlement predominantly Swedish. The point of origin for Stotler settlers is remembered as Princeton, suggesting that Mellgren was not alone in his Kansas venture. Indeed the present day survival of the “Rapp School” in that community reprises a familiar Princeton name, as does the name Fagerstrom. (In 1968 we were quartered in a house owned by the Rapp family: Grandma Anna Rapp startled me when, at the conclusion of a pastoral call to her farm she took my arm, and with that Smålanning cadence said: “you could be my kid.” I then, and ever since, have loved her kind.)

The relationship of these two mission houses to the local Lutherans cannot be reconstructed, but the Stotlerites experienced an unusual rupture in that a group dissented from them and formed an Augustana congregation. This would indicate that the “old reader” sentiment was strong among the former Princetonians in Kansas, though Mellgren remained apparently with the Mission group. He spent his whole life on his own farm nearby and is buried there.

The Rapp School near Stotler, and C. P. Mellgren's marker

Though the famous Skogsbergh visit to Princeton and that of evangelist Billy Sunday are covered in the 40th anniversary book, no mention is made of an earlier visit by none other than D. L. Moody:

In March of 1861, Moody traveled to Princeton, Illinois, to speak at a Sunday-School Convention where he was “thrust into a new role, speaking to Sunday school teachers at a large church.” W. H. Daniels stated “This was the beginning of a wide-spread revival in Bureau County,” and “it was also the beginning of a new life for Mr. Moody.” W. H. Daniels, D. L. Moody and His Work (Hartford: American Publishing Co., 1875) 159–161.

This fact was unearthed by David M. Gustafson in “Moody and the Swedes.” We can only speculate on the influence this visit may have had on C. G. Swanson when he traveled up to Chicago to invite the “Swedish Moody” to come to Princeton.

The result was that the mission group, which had recently doubled in size, now doubled again! The large new building which rose on main street was now, whatever the constitution might have read, becoming the Swedish church in Princeton! But the evangelical mass-meeting went beyond the comfort zone of Pastor Wedin, and he left to become a traveling preacher in Nebraska under the auspices of the Augustana mission work there. He also sojourned briefly in Stotler, Kansas, preaching “in a schoolhouse” near his friend Mellgren.

Peter Wedin in American, and at Sunnerbo, Sweden

Young Pastor August Eckerberg is called following Wedin, and his ministry is cut tragically short by his early death. A highlight of his brief time there was his marriage to Louisa Swanson, the church organist. The ceremony was performed by Andrew Hallner, with music by J. A. Hultman.

The relationship between Skogsbergh and Princeton was forever enhanced by the often-quoted words from his memoirs: that Princeton was “a shining star in the Illinois missionfield heavens” and “a light on a candlestick and a city on a hill.” The 40th anniversary story marks this, and some other fond memories of the Skogsbergh visit. Two farmers have just attended an auction at which they bought a bull. Returning home with their acquisition, they realize that they will be late to the revival meeting. Encountering another man, they resell the bull to him, and arrive in time for the life-changing event. Another, who at that writing was the church chairman, is pursuing his work as a well-digger. He, too, is late and arrives at the revival in his muddy, high boots. His only choice of seats is in the front row; a choice probably not popular with the custodian of the Presbyterian church in which the meetings were held!

But pastor Wedin, the historian continues, could not approve of this new movement; he sat as a silent delegate in the assembly. Up on the south side of Chicago, a Swedish Baptist pastor was urged to try some of Skogsbergh’s methods. Objecting to the kind of style employed, his answer was, “I don’t have it in me.” Perhaps Wedin felt the same, and perhaps it was more a matter of style than substance.

In a bit of historic irony, we finally located his grave in Hamilton county, where he rests near the gravesite of Skogsbergh’s mother in the Monroe Free churchyard. So many Princetonians had moved to Nebraska, that this area was known as the “Princeton Settlement” (later, for Monroe, it became the “Chicago Settlement” as detailed in the Hamilton county section). We knew none of this in 1968.

Peter Wedin gravesite in Hamilton county, Nebraska

At this time, 1877, the Swedish Baptists who had earlier bypassed Princeton (according to Norelius) also made an appearance. Adolph Olson is our source:

“Princeton, located in the same area (as Altona) and due east of Moline, was settled by Swedes as early as 1850. A Lutheran church was formed there in 1854. By 1877, or a bit earlier a few immersed believers from Sweden had come to Princeton. These invited John Ongman, then pastor in Chicago, to hold a series of gospel services, with the result that several of the Swedes in Princeton believed on the Lord and were saved. On February 4, 1877, ten of the converts were immersed. A week later eight more followed the Lord in baptism. As the Swedes of the city had never witnessed a New Testament baptism before, it caused much excitement and some opposition, since the Baptists were regarded as the rankest kind of heretics. A Swedish Baptist church, with twenty-one charter members, was organized February 15, 1877. Under the powerful preaching of Christopher Silene, who served as pastor during the first three years, forty new members were added to the church. Undoubtedly that was the most productive period the Princeton church ever had. For some fifty years, or more, the fellowship of immersed believers, never reaching a membership much over fifty, kept the gospel light burning, until in the nineteen-thirties the church disappeared from the Conference records.” (Olson p.261)

It would stand to reason that with the passage of the Swedish language, there was no good reason not to join with the American Baptists, whose church remained active in 1968 and whose pastor participated in the local ministerium with the rest of us. The Free church leaned toward adult baptism as well, but typically emphasized the “baptism of the Holy Spirit” while deemphasizing traditional sacraments, something that was less true of the Swedish Baptists. Princell’s Ansgar congregation, coming up, would have no doubt followed his traditional Lutheran practice regarding baptism.

There is something of a mystery in the story of Princeton’s mission friend congregation. That mystery is brought to light in Karl Olsson’s treatment of the “independents”… those churches that in the 1870’s were said to have formed without affiliating with any synodic organization or who “withdrew” from such synods as they may have formerly joined. He specifically mentions Princeton as one of these.

But one looks in vain in any recent Princeton anniversary book for a chapter on this story. Evidently once their lot had been cast with the new Forbund in 1885 this part of the story “dropped out.” Or, is it possible to reconstruct some insight into this phase from the 1908 40th anniversary account? Here, the writer of that history takes pains to remind the reader of some fine points in the förening vs. församling issue. While, in 1873, the group had joined the Mission Synod as a “congregation,” it had never altered its original constitution as an “association.” This remained the case when in 1876, the Mission Synod redrew its constitutional boundaries to qualify its allegiance to the Augsburg Confession and the Lutheran symbolic books; limiting their authority to content which could be shown consistent with Holy Scripture. Princeton delegates affirmed this revision, but did not alter their constitutive name.

In the absence of a clear narrative, one might speculate that Princeton decided to revert to an earlier status; a “pre-synodic” association if you will. But when the troublesome terms of synod and confession were abandoned in the 1885 organization in Chicago, Princeton was back on board…as a “congregation”; a “church.” A similar situation existed in Skogsbergh’s Minneapolis tabernacle and the one he had organized on Chicago’s south side, pointing to the possibility that his influence was a factor in Princeton as well, where he was understandably held in high regard.

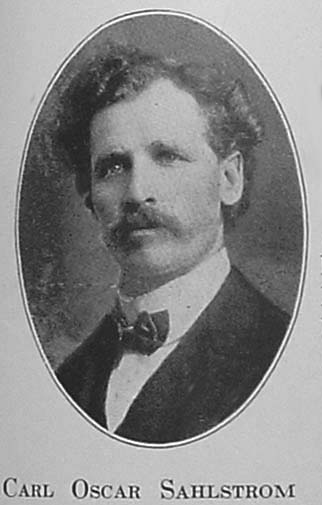

Though the issue above may be obscure, the helgelse or holiness, episode is treated fully. Even Pastor C. O. Sahlström, who was a part of this movement, is given space in the 40th book. Since his mother lived in Princeton, he frequently returned after this affair was over, and was not forbidden from preaching in the Covenant church. Several historical accounts attribute this holiness movement to the influence of a Free Methodist tent meeting campaign in Princeton. Sahlström does not deny this, he admits being present at that event, but insists that his own searching of scriptures had led him in this direction. These relevant passages he lists in detail. He even cites the authority of Fredrik Franson on the matter. Obviously there was quite a number of those subscribing to this new idea of sinlessness, and as they are about to join the Mission group the board puts the idea “on hold.” Sensing problems, this group forms its own free mission congregation. There had been persistent debates at board meetings, and that body had finally expelled four of the most vociferous holiness advocates.

These notions, as Sahlström observes, were also afoot in Sweden and some Princeton immigrants may have been disposed in this direction. It is also true that the Swedish Methodists had been plagued by those advocating a doctrine of sinless perfection in this life. Since this was a tenet of the Bishop Hill Janssonites, the many defectors from that commune were observed to tend in that direction. (for an excellent contemporary report on the Bishop Hill community, see the SAAG items #91 and #92 at the NPC Archives website) While unpleasant to recall, the Princeton historian observes that “a storm clears the air.”

Sahlström found a home among the Free churches of Nebraska, where he is remembered along with his large family by descendants of the Phelps Center church…in later years enjoying the hobby of working on clocks. The well-known Mission pastor, Adam Lidman succeeds him at Princeton. Lidman would also serve an interim pastorate in Wausa, Nebraska. Another Wausa pastor, Fritz Hjelm would reverse this course, moving from Wausa to Princeton. We were just beginning to learn these things in 1968.

While the air was clearing for the Mission congregation, there were clouds on the horizon over at the Lutheran church. In 1882 Rev. S. A. Sandahl (we know of no connection with the Nebraska Sandahl) leads the congregation in adopting the newest revision of the Augustana constitution. It forbids membership to those belonging to secret societies. Fifty-six members leave, and as many as eighty join together in a new group. They seek a minister from the new school at Knoxville; yes, it is Ansgar College; and who should answer their call but J. G. Princell. The historian reminds the readers that it was in the 1878 annual meeting held in Princeton that Augustana had defrocked Princell. Now he assists in the forming of the Swedish Lutheran Emanuel Congregation, Princeton, Illinois! High irony indeed.

Princeton Covenant Church in 1953

The names associated with this group are remarkable. We have S. O. Josephson and Swan Pierson; Hed and Nordberg among the laymen. (did the name “Hed” become “Hade”?) Student pastors come from Knoxville: John Hägström, F. M. Johnson, E. G. Hjerpe, A. W. Franklin and G. Gustafson. These future Covenant leaders were then all students of Princell. When this congregation disbands in 1884, some join the Free group originated in C. O. Sahlström’s day and twenty become members of the Mission group. This was a colorful chapter in Princeton history! When the Free congregation disbanded, or even where they met, is unknown. To recap the situation, the Swedish Lutheran church had endured two ruptures; first the southeast settlement mission friends, who then spawned a free mission group, and then an Ansgar congregation, which was short-lived but contributed more former Lutherans to the mission and free mission groups!

Princeton's Conference institution: the Childrens' Home

Many descendants of the Mission Friends made their first acquaintance with the name, Princeton, in connection with Sunday School fund raising for the Princeton Children’s Home. Begun in about 1920, this institution of the Illinois Conference was another “shining light” at Princeton for generations. Acquaintances among their staff have endured also in memory: Dr. K. M. Nelson, a major force in the home's success; the Rev. Richard Petersons; Laverne Person of Swedeburg; and Roger and Adele Lundeen who later served the Buffalo, MN, Ebenezer Home.

Those most responsible for the priceless opportunity afforded us in 1968 were the patient and longsuffering director of North Park Seminary internships, Dr. Earl Dahlstrom and Princeton senior pastor Ron Lagerstrom. Their tolerance and understanding has only grown in my estimation.

Princeton Covenant Church in 1968

The centennial history has the story of the obvious addition on the left: "An occasion which created much interest in the congregation was the dedication of the new educational unit in 1953. Two years earlier the Catholic Church, located on the southeast of Main and Central in the same block as the Covenant Church, offered their lot, church and parsonage for sale. The property was purchased for $22,500 and the church building was moved across the lot and attached to the existing Covenant Church where it was remodeled into the present educational unit. The Catholic rectory, also located on this property, was moved to South Euclid just north of Peru and became the new Covenant parsonage, replacing the former parsonage on Church Street."

There is something else that should be mentioned in connection with the Princeton Covenant church and its aspiration, mentioned above, to be the Swedish church in Princeton. Perhaps in the interest of serving the broadest range of the immigrants, the Princeton church is noted for preserving such features as vestments for its clergy, a divided chancel, and observance of the church year. During the centennial year, one visiting Covenant pastor chafed at the thought of wearing a robe...did not do so...and warned the congregation against "churchianity."

Time and space fail to afford all that might be mentioned in connection with Princeton: former pastors such as A. A. Magnusson, who also ventured west to Malmo, Nebraska (see that section); the Pamps; Wm. Freeman, who became an institution at Omaha; A. M. Bowman; Don Frisk, who left Princeton as a young man to become a pillar of North Park Seminary and lived to nearly one hundred years of age; Glenn Wiberg, whose recorded sermons were still played for shut-ins in 1968; and John Weborg, whose course took him from Nebraska, to Princeton, to North Park Seminary faculty and back to Princeton.

Finally, an aspect of 1968 in Princeton which has endured was the opportunity to train for the pilots’ certificate at Mays’ airport. (see the aviation section) It truly was a year that would last a lifetime.

Princeton Covenant Church today